Melbourne Modern: the Legacy of European Artists and Designers

RMIT University Gallery

This exhibition at the RMIT Gallery traced the lasting impact of European influence on generations of RMIT teachers and students to the present day.

In the wake of World War II, hundreds of exiled and displaced European artists, architects and designers arrived in Melbourne. Many found employment at RMIT, in what was then Melbourne Technical College, bringing with them their rigorous training and bold philosophical ideas about modernism.

Curated by 2018 Ursula Hoff Fellow at the University of Melbourne Dr Jane Eckett, and Director of the RMIT Design Archives and Professor of architectural history Harriet Edquist, the exhibition tells a fascinating and complicated story of the impact of emigré educators. Eckett said European migrants were vital to Melbourne’s post-war modernist transformation.

“They were responsible for many mid-century modernist buildings; contributed to debates around town planning and designed notable abstract public artworks – from fountains to murals,” she said.

“They also introduced the latest German and Scandinavian design in gold and silversmithing, as well as fine European tailoring in the fashion industry, and a range of modernist approaches to fine art.”

These emigré educators include architects Ernest Fooks, Frederick Romberg and Frederick Sterne; artists Tate Adams, Richard Beck, Gus van der Heyde, Hermann Hohaus, Vincas Jomantas, Inge King, Hertha Kluge-Pott, Udo Sellbach, Teisutis Zikaras and Klaus Zimmer; and versatile designers such as Gerard Herbst, Adrianus Janssens, George Kral and Miloslav Zika, who worked variously in graphic design, fashion, industrial design, stained glass and art history.

The impact of gold and silversmiths Hendrik Forster, Ernst Fries, Johannes Kuhnen, Tor Schwanck, Victor Vodicka and Wolf Wennrich was far reaching.

Trained in Germany, Wennrich became the most influential jewellery lecturer of the 1960s and 70s in the RMIT Gold and Silversmithing studio, encouraging students to think of themselves as artists and pursue their own designs.

“These artists and designers did not bring with them one single monolithic modernism, but rather a constellation of ideas and philosophies that reflected their individual experiences as well as a long European lineage of technical education and design reform,” Eckett said.

This approach to modernism in architecture suited Australia, as it advocated informality and flexibility.

Common to most was the desire for an interdisciplinary approach to education, whereby architects studied sculpture, sculptors studied design, and designers studied painting.

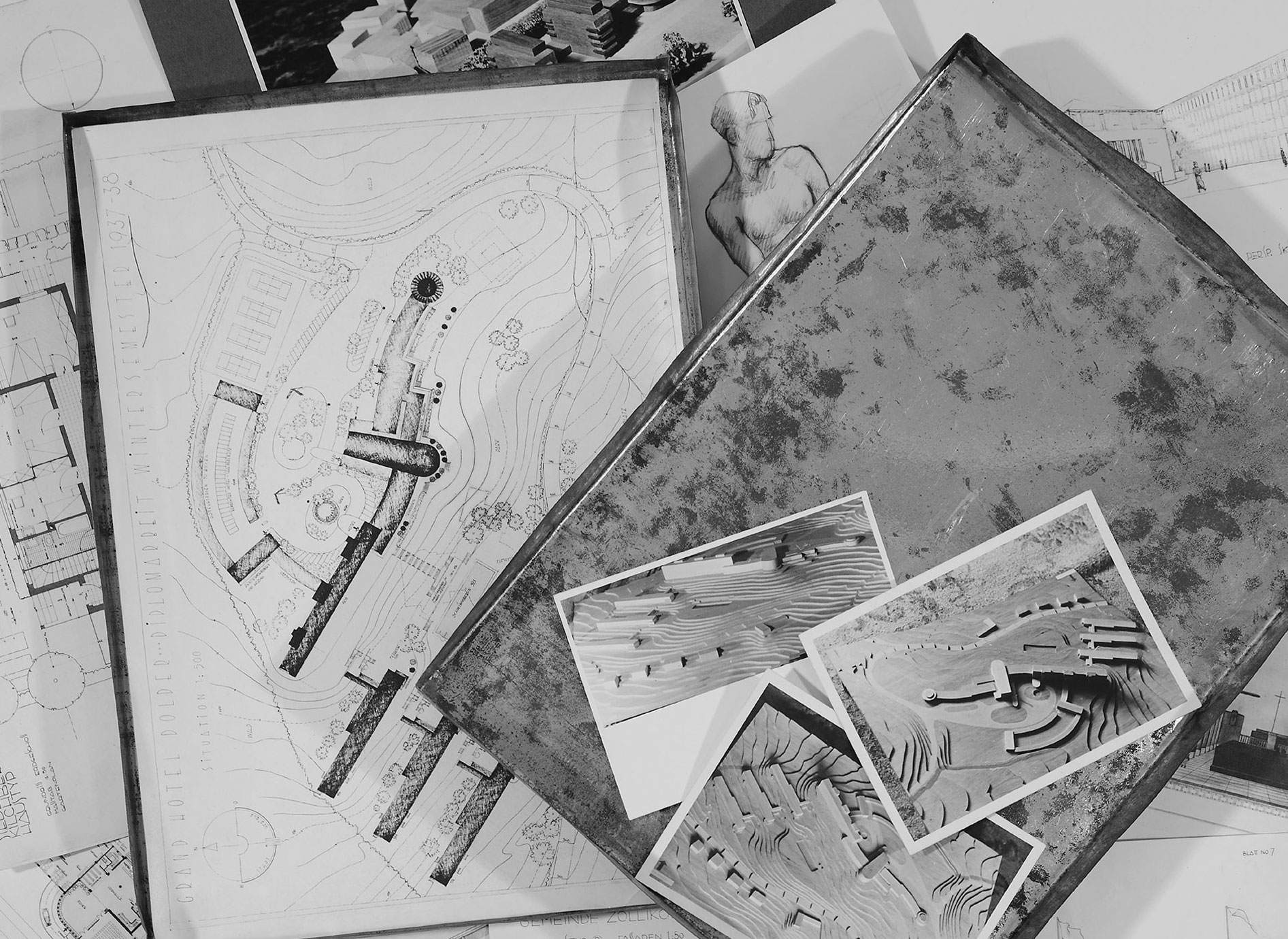

Reflecting this interdisciplinary cross-pollination, the exhibition features works in a wide variety of media including painting, sculpture, prints, stained glass, silver, textiles, photography and film, as well as posters, architectural presentation drawings, student experiments in material studies, product prototypes and rare archival material.

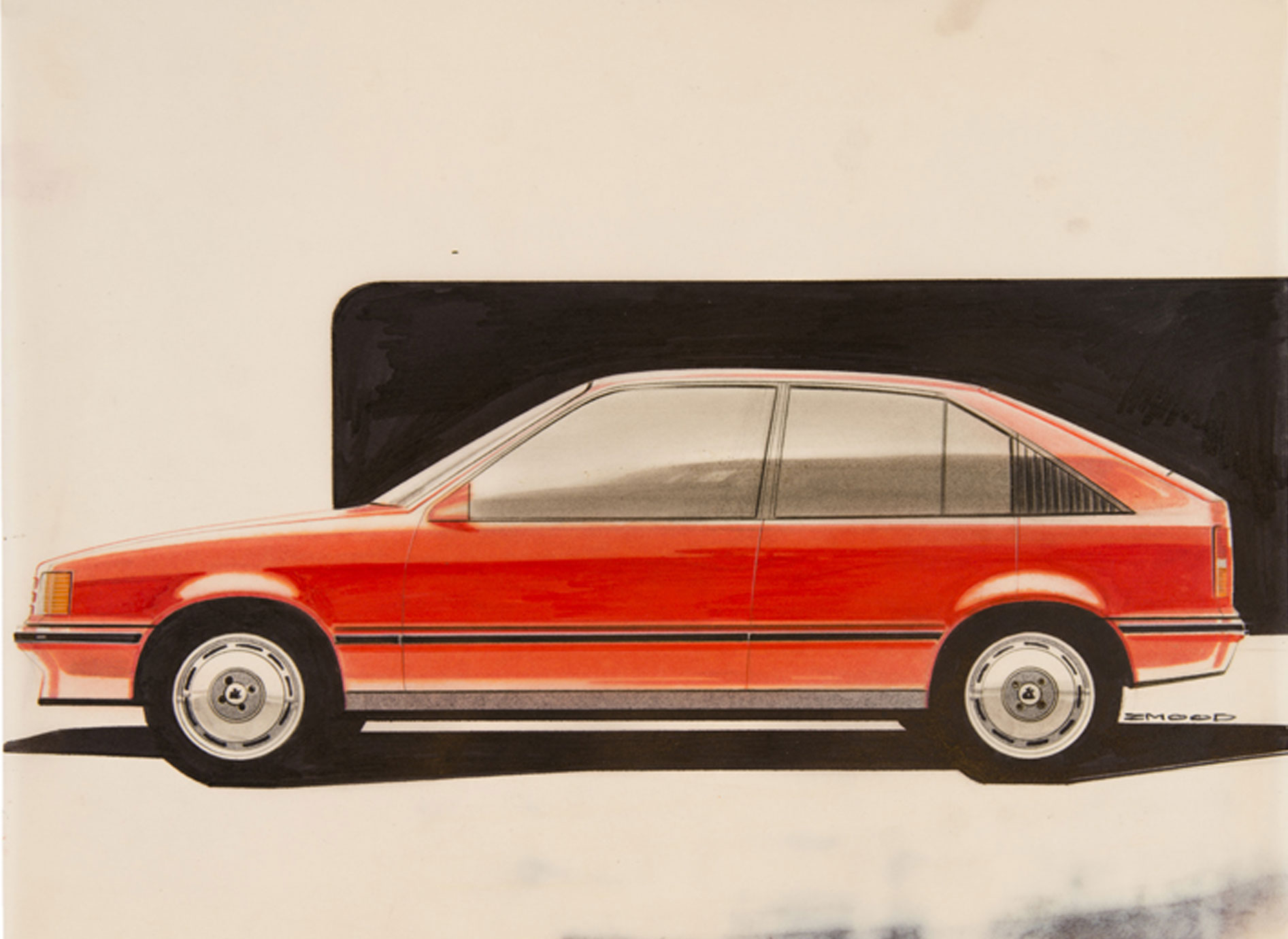

One of RMIT University’s most acclaimed alumni, automotive designer Philip Zmood had a hand in designing iconic Australian cars like the Holden Monaro, Commodore and Kingswood in his role as Australian Director of Design of GM Holden.

The impact and significance of other emigré educators can be seen in the works of subsequent generations of artists and designers such as Philip Zmood, Geoffrey Bartlett, Susan Cohn, Jock Clutterbuck, Augustine Dall’Ava, John Davis, Emily Floyd, Robert Jacks, Sanné Mestrom, Anthony Pryor and Normana Wight, whose works are also represented in the exhibition.